The basics

Quick summary

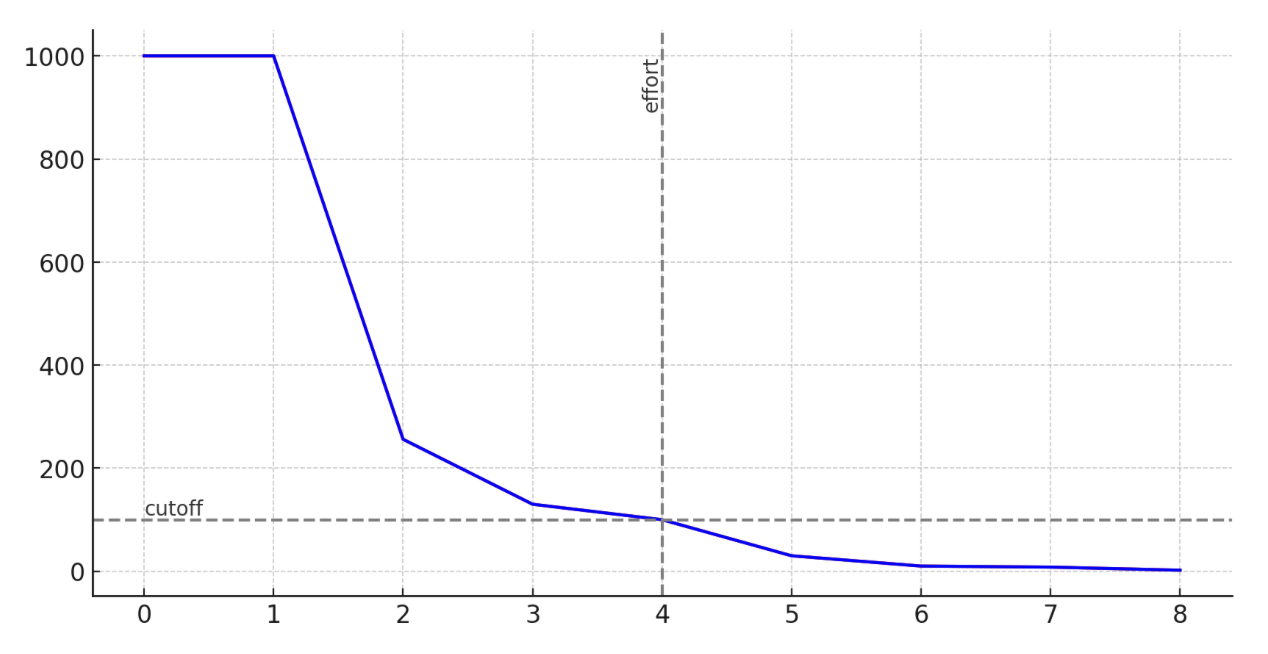

We determine a cutoff point and only perform multiplications that exceed this threshold. This section explains how we select the cutoff and manage calculations, while the following section details the multiplication algorithm that optimizes memory read patterns and achieves high performance on GPUs.

Details

The most time-consuming aspect of LLM inference involves vector-matrix multiplication, where a state vector (h) is multiplied by a weight matrix (w) to produce an output state (o).

Within inference, there are also some attention calculations, but we won't be discussing those here. All other processes take virtually no time.

It’s also crucial to point out that it’s the memory reads, not the multiplications, that deserve our spotlight. We'll dive deeper into this drama in the next chapter.

Let's dive in. Here's a miniature version of the behemoth we're up against.

\[ \begin{bmatrix} h_{1} \\ h_{2} \\ h_{3} \end{bmatrix} \times \begin{bmatrix} w_{11} & w_{12} & w_{13} \\ w_{21} & w_{22} & w_{23} \\ w_{31} & w_{32} & w_{33} \end{bmatrix} \] \[=\] \[ \begin{bmatrix} h_{1} \cdot w_{11} + h_{2} \cdot w_{21} + h_{3} \cdot w_{31} \\ h_{1} \cdot w_{12} + h_{2} \cdot w_{22} + h_{3} \cdot w_{32} \\ h_{1} \cdot w_{13} + h_{2} \cdot w_{23} + h_{3} \cdot w_{33} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} o_1 \\ o_2 \\ o_3 \end{bmatrix} \] For a concrete example. \[ \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 10 \\ 1000 \end{bmatrix} \times \begin{bmatrix} 2 & 8 & 256 \\ 13 & 1 & 3 \\ 1 & 0.1 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \] \[=\] \[ \begin{bmatrix} 1 \cdot 2 + 10 \cdot 13 + 1000 \cdot 1 \\ 1 \cdot 8 + 10 \cdot 1 + 1000 \cdot 0.1 \\ 1 \cdot 256 + 10 \cdot 3 + 1000 \cdot 1 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 1132 \\ 118 \\ 1286 \end{bmatrix} \] An initial instinct might be to remove the weights with the lowest values. \[ \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 10 \\ 1000 \end{bmatrix} \times \begin{bmatrix} 2 & 8 & 256 \\ 13 & & 3 \\ & & \end{bmatrix} \] but look what happened to the output! \[ \begin{bmatrix} 1 \cdot 2 + 10 \cdot 13 \\ 1 \cdot 8 \\ 1 \cdot 256 + 10 \cdot 3 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 132 \\ 8 \\ 556 \end{bmatrix} \] At first glance, the changes appear significant.

Some issues can be mitigated by normalization; however, the value in the second dimension remains significantly lower than originally, while the third dimension's value is much higher

Even a seemingly insignificant weight, like 0.1, can punch above its weight class if it's lucky enough to pair with a high vector value—1000 in this scenario.

Now, let's normalize the vectors and calculate their distance, or cosine similarity score: \[ d(\ \begin{bmatrix} 0.67 \\ 0.07 \\ 0.75 \end{bmatrix} , \begin{bmatrix} 0.23 \\ 0.01 \\ 0.97 \end{bmatrix} ) = 0.88 \] This approach is effective to some extent; it resembles how distillation functions. For instance, quantization might replace a weight of 0.1 with 0, and weights of 1 with 2, as seen in this example. Similar adjustments occur in techniques like LORA and PCA. (This section requires further details.)

However, let's consider another, more dynamic approach. Instead of making static changes to the matrix, we'll now concentrate on the multiplications and select only the top one or two from each output.

Let's start by sorting the multiplications row-wise.

\[ \begin{bmatrix} 1000 \cdot 1 + 10 \cdot 13 + 1 \cdot 2 \\ 1000 \cdot 0.1 + 10 \cdot 1 + 1 \cdot 8 \\ 1000 \cdot 1 + 1 \cdot 256 + 10 \cdot 3 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 1132 \\ 118 \\ 1286 \end{bmatrix} \] Now, let's remove the least significant multiplications from each row. \[ \begin{bmatrix} 1000 \cdot 1 + 10 \cdot 13 \\ 1000 \cdot 0.1 + 10 \cdot 1 \\ 1000 \cdot 1 + 1 \cdot 256 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 1130 \\ 110 \\ 1256 \end{bmatrix} \] \[ \begin{bmatrix} 1000 \cdot 1 \\ 1000 \cdot 0.1 \\ 1000 \cdot 1 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 1000 \\ 100 \\ 1000 \end{bmatrix} \] That's quite efficient! Even with this last example, we're performing fewer multiplications—and consequently fewer memory reads—than with the previous method, and the results are already noticeably better.

Let's see our score. \[ cosSim(\ \begin{bmatrix} 1130 \\ 110 \\ 1256 \end{bmatrix} , \begin{bmatrix} 1132 \\ 118 \\ 1286 \end{bmatrix} ) = 0.999 \] \[ cosSim(\ \begin{bmatrix} 1000 \\ 100 \\ 1000 \end{bmatrix} , \begin{bmatrix} 1132 \\ 118 \\ 1286 \end{bmatrix} ) = 0.997 \]

Look at that!

We're now performing only a third of the calculations compared to before, and our similarity score is so close to 1 that even the most discerning transformer would likely not detect a difference!

However, there is one issue: to execute this operation, we must first perform all the multiplications and then sort them, which might seem somewhat counterproductive.

I explored several methods but couldn't find one that specifically allows for this approach.

Instead, we'll flip the matrix, sort the elements row-wise, and reconsider the multiplications from this new perspective. \[ \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 10 \\ 1000 \end{bmatrix} \times \begin{bmatrix} 256 \scriptstyle \searrow 3 & 8 \scriptstyle \searrow 2 & 2 \scriptstyle \searrow 1 \\ 13 \scriptstyle \searrow 1 & 3 \scriptstyle \searrow 3 & 1 \scriptstyle \searrow 2 \\ 1 \scriptstyle \searrow 1 & 1 \scriptstyle \searrow 3 & 0.1 \scriptstyle \searrow 2 \end{bmatrix} \] This is known as the Compressed Sparse Row (CSR) format. To perform the multiplication now, we might take the 1 from the vector, multiply it by 256, and place the result in the third row of the output vector, and so forth.

Let's observe what happens when we truncate the last column, which contains the lowest values. \[ \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 10 \\ 1000 \end{bmatrix} \times \begin{bmatrix} 256 \scriptstyle \searrow 3 & 8 \scriptstyle \searrow 2 \\ 13 \scriptstyle \searrow 1 & 3 \scriptstyle \searrow 3 \\ 1 \scriptstyle \searrow 1 & 1 \scriptstyle \searrow 3 \end{bmatrix} \rightarrow \begin{bmatrix} 10 \cdot 13 + 1 \cdot 1000 \\ 8 \cdot 1 \\ 256 \cdot 1 + 3 \cdot 10 + 1 \cdot 1000 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 1130 \\ 8 \\ 1286 \end{bmatrix} \] The results are quite close! \[ cosSim(\ \begin{bmatrix} 1130 \\ 8 \\ 1286 \end{bmatrix} , \begin{bmatrix} 1132 \\ 118 \\ 1286 \end{bmatrix} ) = 0.998 \] This score of 0.998 was achieved with 66% of the multiplications, which is less efficient than our optimal algorithm at 33%. Essentially, this is a static distillation method where we simply remove the smallest weights from each row.

This small example also illustrates an issue of under-serving the output dimensions—if we reduce the array to just one column, the middle dimension of the output vector would have no data.

In my personal experiments with actual data and transformers, the results begin to degrade quite rapidly after the removal of 30% weights. Interestingly, the final implementation enables truncation of the last rows, which saves memory without significantly reducing quality—mainly because these rows aren't utilized at lower effort levels. However, I'm getting a bit ahead of myself here.

Recall our earlier discussion: even a tiny weight of 0.1 in the last row becomes significant if it multiplies against a 1000 in the input vector.

Therefore, we need a better, more dynamic solution—one that also considers the input vector.

First, let’s step back, perform all the necessary calculations, and then sort them. \[ \begin{bmatrix} 1 \cdot 256 & 1 \cdot 8 & 1 \cdot 2 & 10 \cdot 13 & 10 \cdot 3 & 10 \cdot 1 & 1000 \cdot 1 & 1000 \cdot 1 & 1000 \cdot 0.1 \end{bmatrix} \] \[ \downarrow \] \[ \begin{bmatrix} 1000 & 1000 & 256 & 130 & 100 & 30 & 10 & 8 & 2 \end{bmatrix} \]

Now, suppose we decide to perform only 5 out of the 9 necessary calculations...

In this example, our cutoff point is at 100. This also introduces our first mention of the 'effort' metric.

Effort is how many calculations we want to perform out of all the ones that would be necessary. 100% effort is a plain old matrix multiplication. 0% effort is what I spent checking if someone invented all of this before me.

Now that we understand the 'effort' metric, let’s revisit the sorted matrix multiplication.

A bit of pseudocode first

cutoff = calc_cutoff(effort)

def approxMul(V, W):

for el_v in V:

el_cutoff = cutoff / el_v

for el_w, idx_w in W:

if el_w > el_cutoff:

O[idx_w] += el_v * el_w

else:

break

# other els in the rows are smaller,

# so we can skip checking them

With this code and a cutoff of 100 in mind, let's revisit our calculations: \[ \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 10 \\ 1000 \end{bmatrix} \times \begin{bmatrix} 256 \scriptstyle \searrow 3 & \cancel{\textcolor{gray}8 \scriptstyle \searrow 2} & \cancel{\textcolor{gray}2 \scriptstyle \searrow 1} \\ 13 \scriptstyle \searrow 1 & \cancel{\textcolor{gray}3 \scriptstyle \searrow 3 } & \cancel{\textcolor{gray}1 \scriptstyle \searrow 2 } \\ 1 \scriptstyle \searrow 1 & 1 \scriptstyle \searrow 3 & 0.1 \scriptstyle \searrow 2 \end{bmatrix} \] \[=\] \[ \begin{bmatrix} 1 \cdot 1000 + 13 \cdot 10 \\ 0.1 \cdot 1000 \\ 1 \cdot 1000 + 256 \cdot 1 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} 1130 \\ 100 \\ 1256 \end{bmatrix} \] The 0.1 weight made the cut, with 55% of the calculations completed! \[ cosSim(\ \begin{bmatrix} 1130 \\ 100 \\ 1256 \end{bmatrix} , \begin{bmatrix} 1132 \\ 118 \\ 1286 \end{bmatrix} ) = 0.99989 \] Nice! We were fortunate here—if we had chosen a slightly lower effort level, we would have missed the 100, and the entire middle row of the result would have become unbalanced. Fortunately, in the real world with 4kx12k matrices, these issues tend to even out.

In practice, this method requires slightly more effort—meaning more calculations—than our previous approach to achieve the same result. However, it is nearly implementable, unlike the previous method.

Now, we just have three challenging details to resolve, and we'll be ready to proceed.

Firstly, to determine the cutoff, we need to perform and sort all the calculations. I mentioned earlier that we could do this without completing all calculations. Am I contradicting myself? Certainly not. The solution, while simple, is more applicable to real-world arrays than to this particular example.

In the real world, arrays are at least 4k by 12k in size (like those in Mistral). The effort-cutoff charts for these arrays resemble what you've seen previously. Here's an example of such a chart:

(tbd, sorry)

The shape is consistently similar; however, it varies—becoming wider or shallower—depending on the matrix-vector combination.

Potentially, there is an underlying mathematical principle for dynamically selecting the optimal effort/cutoff based on this shape, such as ensuring the areas to the left and right of the effort are similar. I have experimented with this concept, but for now, I have opted to continue with a static effort approach.

Additionally, it's important to note that real-world matrices and vectors contain both positive and negative numbers. This fact slightly complicates matters, as more effort is required to achieve the same cosine similarity score, though it also reduces the likelihood of drift.

Fortunately, since the weight matrices and input vectors are neatly disorganized, we can effectively choose a small subset of all multiplications that will closely represent the overall chart.

(tbd)

So, what do we do in practice?

probes = []

for i in 0..min(inDim, outDim):

probes[i] = W[i, i]

During the precomputation phase, in addition to sorting the matrices, we select a random weight for each input dimension from the matrix. Given the matrix's neatly disorganized nature, we can traverse the diagonal—a method generally discouraged for other types of matrices.

We'll refer to these weights as 'probes'.

The "final" algorithm is as follows:

def precompute(W):

W = W.T

probes = get_probes(W)

W_idx, W_val = sortMatrixRows(W)

def approxMul(v, W_idx, W_val, probes):

cutoff_chart = v * probes

cutoff = topK(cutoff_chart, effort)

# the rest is the same as beffore

for el_v in V:

el_cutoff = cutoff / el_v

for el_w, idx_w in W:

if el_w > el_cutoff:

O[idx_w] += el_v * el_w

else:

break

# other els in the rows are smaller,

# so we can skip checking them

TIn this way, we develop an algorithm that operates with only a number of calculations determined by the effort level and still delivers an excellent output approximation.

A beautiful algorithm—one that our grandfather would be proud of.However, our grandfather lived before the era of GPUs.

In those days, calculations were crucial, not memory accesses. If implemented today, this algorithm could embarrass our family, drawing laughter and pointing fingers from children if we were to use such a monstrosity.

However, there are still two significant challenges to overcome on our path to victory.

- - our matrices now store both values and indexes - doubling the memory

- our algorithm performs random memory writes, particularly evident in the following line:

O[idx_w] += el_v * el_w

this involves random memory access to idx_w, complicating parallelization as multiple threads may attempt to write to the same O[idx_w].

"As of my last update, I am not aware of any solutions specifically addressing this approach to matrix multiplication optimization for LLM inference." — ChatGPT Up until this point, we still haven't reached new territory. People have faced this issues before, but as of writing this text, I didn't find a published solution to solve it properly. GPT-4 wasn't aware of it either.

So buckle up, my friend, and prepare for a wild ride ahead.

Our adventure continues.

And later on...

- Pesky details (or Help Needed!)

And of course...

- Citations, notes and so on